- Home

- Cheryl Mullenax (Ed)

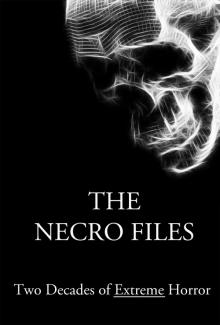

Necro Files: Two Decades of Extreme Horror Page 4

Necro Files: Two Decades of Extreme Horror Read online

Page 4

* * *

They made him pay first, before he could even enter the booth. Then he sat there for an hour while they found her and punched through. Finally, though, finally; “Josie.”

“Greg,” she said, grinning her distinctive grin. “I should have known. Who else would call all the way from Vendalia? How are you?”

He told her.

Her grin vanished. “Oh, Greg,” she said. “I’m sorry. But don’t let it get to you. Keep going. The next one will work out better. They always do.”

Her words didn’t satisfy him. “Josie,” he said, “How are things back there? You miss me?”

“Oh, sure. Things are pretty good. It’s still Skrakky, though. Stay where you are, you’re better off.” She looked offscreen, then back. “I should go, before your bill gets enormous. Glad you called, love.”

“Josie,” Trager started. But the screen was already dark.

* * *

Sometimes, at night, he couldn’t help himself. He would move to his home screen and ring Laurel. Invariably her eyes would narrow when she saw who it was. Then she would hang up.

And Trager would sit in a dark room and recall how once the sound of his voice made her so very, very happy.

* * *

The streets of Gidyon are not the best of places for lonely midnight walks. They are brightly lit, even in the darkest hours, and jammed with men and deadmen. And there are meathouses, all up and down the boulevards and the ironspike boardwalks.

Josie’s words had lost their power. In the meathouses, Trager abandoned dreams and found cheap solace. The sensuous evenings with Laurel and the fumbling sex of his boyhood were things of yesterday; Trager took his meatmates hard and quick, almost brutally, fucked them with a wordless savage power to the inevitable perfect orgasm. Sometimes, remembering the theatre, he would have them act out short erotic playlets to get him in the mood.

* * *

In the night. Agony.

He was in the corridors again, the low dim corridors of the corpsehandlers’ dorm on Skrakky, but now the corridors were twisted and torturous and Trager had long since lost his way. The air was thick with a rotting gray haze, and growing thicker. Soon, he feared, he would be all but blind.

Around and around he walked, up and down, but always there was more corridor, and all of them led nowhere. The doors were grim black rectangles, knobless, locked to him forever; he passed them by without thinking, most of them. Once or twice, though, he paused, before doors where light leaked around the frame. He would listen, and inside there were no sounds, and then he would begin to knock wildly. But no one ever answered.

So he would move on, through the haze that got darker and thicker and seemed to burn his skin, past door after door after door, until he was weeping and his feet were tired and bloody. And then, off a ways, down a long, long corridor that loomed straight before him, he would see an open door. From it came light so hot and white it hurt the eyes, and music bright and joyful, and the sounds of people laughing. Then Trager would run, though his feet were raw bundles of pain and his lungs burned with the haze he was breathing. He would run and run until he reached the room with the open door.

Only when he got there, it was his room, and it was empty.

* * *

Once, in the middle of their brief time together, they’d gone out into the wilderness and made love under the stars. Afterwards she had snuggled hard against him, and he stroked her gently. “What are you thinking?” he asked.

“About us,” Laurel said. She shivered. The wind was brisk and cold. “Sometimes I get scared, Greg. I’m so afraid something will happen to us, something that will ruin it. I don’t ever want you to leave me.”

“Don’t worry,” he told her. “I won’t.”

Now, each night before sleep came, he tortured himself with her words. The good memories left him with ashes and tears; the bad ones with a wordless rage.

He slept with a ghost beside him, a supernaturally beautiful ghost, the husk of a dead dream. He woke to her each morning.

* * *

He hated them. He hated himself for hating.

3

Duvalier’s Dream

Her name does not matter. Her looks are not important. All that counts is that she was, that Trager tried again, that he forced himself on and made himself believe and didn’t give up. He tried.

But something was missing. Magic?

The words were the same.

How many times can you speak them, Trager wondered, speak them and believe them, like you believe them the first time you said them? Once? Twice? Three times, maybe? Or a hundred? And the people who say it a hundred times, are they really so much better at loving? Or only at fooling themselves? Aren’t they really people who long ago abandoned the dream, who use its name for something else?

He said the words, holding her, cradling her, and kissing her. He said the words, with a knowledge that was surer and heavier and more dead than any belief. He said the words and tried, but no longer could he mean them.

And she said the words back, and Trager realized that they meant nothing to him. Over and over again they said the things each wanted to hear, and both of them knew they were pretending.

They tried hard. But when he reached out, like an actor caught in his role, doomed to play out the same part over and over again, when he reached out his hand and touched her cheek—the skin was smooth and soft and lovely. And wet with tears.

* * *

IV

Echoes

“I don’t want to hurt you,” said Donelly, shuffling and looking guilty, until Trager felt ashamed for having hurt a friend.

He touched her cheek, and she spun away from him.

“I never wanted to hurt you,” Josie said, and Trager was sad. She had given him so much; he’d only made her guilty. Yes, he was hurt, but a stronger man would never have let her know.

“I’m sorry, I don’t,” Laurel said. And Trager was lost. What had he done, where was his fault, how had he ruined it? She had been so sure. They had had so much.

He touched her cheek, and she wept.

How many times can you speak them, his voice echoed, speak them and believe them, like you believed them the first time you said them?

The wind was dark and dust heavy, the sky throbbed painfully with flickering scarlet flame. In the pit, in the darkness, stood a young woman with goggles and a filtermask and short brown hair and answers. “It breaks down, it breaks down, it breaks down, and they keep sending it out,” she said. “Should realize that something is wrong. After that many failures, it’s sheer self-delusion to think the thing’s going to work right next time out.”

The enemy corpse is huge and black, its torso rippling with muscle, a product of months of exercise, the biggest thing that Trager has ever faced. It advances across the sawdust in a slow, clumsy crouch, holding the gleaming broadsword in one hand. Trager watches it come from his chair atop one end of the fighting arena. The other corpsemaster is careful, cautious.

His own deadman, a wiry blond, stands and waits, a morningstar trailing down in the blood-soaked arena dust. Trager will move him fast enough and well enough when the time is right. The enemy knows it, and the crowd.

The black corpse suddenly lifts its broadsword and scrambles forward in a run, hoping to use reach and speed to get its kill. But Trager’s corpse is no longer there when the enemy’s measured blow cuts the air where he had been.

Sitting comfortably above the fighting pit/down in the arena, his feet grimy with blood and sawdust—Trager/the corpse—snaps the command/ swings the morningstar—and the great studded ball drifts up and around, almost lazily, almost gracefully. Into the back of the enemy’s head, as he tries to recover and turn. A flower of blood and brain blooms swift and sudden, and the crowd cheers.

Trager walks his corpse from the arena, then stands up to receive applause. It is his tenth kill. Soon the championship will be his. He is building such a record that they can no longer deny him

a match.

* * *

She is beautiful, his lady, his love. Her hair is short and blond, her body very slim, graceful, almost athletic, with trim legs and small hard breasts. Her eyes are bright green, and they always welcome him. And there is a strange erotic innocence in her smile.

She waits for him in bed, waits for his return from the arena, waits for him eager and playful and loving. When he enters, she is sitting up, smiling for him, the covers bunched around her waist. From the door he admires her nipples.

Aware of his eyes, shy, she covers her breasts and blushes. Trager knows it is all false modesty, all playing. He moves to the bedside, sits, reaches out to stroke her cheek. Her skin is very soft; she nuzzles against his hand as it brushes her. Then Trager draws her hands aside, plants one gentle kiss on each breast, and a not-so-gentle kiss on her mouth. She kisses back, with ardor; their tongues dance.

They make love, he and she, slow and sensuous, locked together in a loving embrace that goes on and on. Two bodies move flawlessly in perfect rhythm, each knowing the other’s needs. Trager thrusts, and his other body meets the thrusts. He reaches, and her hand is there. They come together (always, always, both orgasms triggered by the handler’s brain), and a bright red flush burns on her breasts and earlobes. They kiss.

Afterwards, he talks to her, his love, his lady. You should always talk afterwards; he learned that long ago.

“You’re lucky,” he tells her sometimes, and she snuggles up to him and plants tiny kisses all across his chest. “Very lucky. They lie to you out there, love. They teach you a silly shining dream and they tell you to believe and chase it and they tell you that for you, for everyone, there is someone. But it’s all wrong. The universe isn’t fair, it never has been, so why do they tell you so? You run after the phantom, and lose, and they tell you next time, but it’s all rot, all empty rot. Nobody ever finds the dream at all, they just kid themselves, trick themselves so they can go on believing. It’s just a clutching lie that desperate people tell each other, hoping to convince themselves.”

But then he can’t talk anymore, for her kisses have gone lower and lower, and now she takes him in her mouth. And Trager smiles at his love and gently strokes her hair.

* * *

Of all the bright cruel lies they tell you, the cruelest is the one called love.

Night They Missed the Horror Show

Joe R. Lansdale

* * *

“Night They Missed the Horror Show” was originally published in the 1988 anthology Silver Scream, edited by David Schow, from Dark Harvest Press. It later appeared in By Bizarre Hands, a collection of Lansdale’s short stories published by Avon Books, and in High Cotton: Selected Short Stories of Joe R. Lansdale, published in 2000 by Golden Gryphon Press.

“Night They Missed the Horror Show” won a Bram Stoker award for Best Short Story, 1988.

‡

Joe R. Lansdale is the author of over 30 novels and numerous short story collections. His work has been filmed and adapted to comics. He is the editor or co-editor of a dozen anthologies. He has received the Edgar Award, The British Fantasy Award, Seven Bram Stokers, The Grinzani Cavour Prize for literature, and numerous other awards. He lives in Nacogdoches with his wife and near his son and daughter.

* * *

For Lew Shiner, a story that doesn’t flinch

If they’d gone to the drive-in like they’d planned, none of this would have happened. But Leonard didn’t like drive-ins when he didn’t have a date, and he’d heard about Night of the Living Dead, and he knew a nigger starred in it. He didn’t want to see no movie with a nigger star. Niggers chopped cotton, fixed flats, and pimped nigger girls, but he’d never heard of one that killed zombies. And he’d heard too that there was a white girl in the movie that let the nigger touch her, and that peeved him. Any white gal that would let a nigger touch her must be the lowest trash in the world. Probably from Hollywood, New York, or Waco, some god-forsaken place like that.

Now Steve McQueen would have been all right for zombie killing and girl handling. He would have been the ticket. But a nigger? No sir.

Boy, that Steve McQueen was one cool head. Way he said stuff in them pictures was so good you couldn’t help but think someone had written it down for him. He could sure think fast on his feet to come up with the things he said, and he had that real cool, mean look.

Leonard wished he could be Steve McQueen, or Paul Newman even. Someone like that always knew what to say, and he figured they got plenty of bush too. Certainly they didn’t get as bored as he did. He was so bored he felt as if he were going to die from it before the night was out. Bored, bored, bored. Just wasn’t nothing exciting about being in the Dairy Queen parking lot leaning on the front of his ’64 Impala looking out at the highway. He figured maybe old crazy Harry who janitored at the high school might be right about them flying saucers. Harry was always seeing something. Bigfoot, six-legged weasels, all manner of things. But maybe he was right about the saucers. He’d said he’d seen one a couple nights back hovering over Mud Creek and it was shooting down these rays that looked like wet peppermint sticks. Leonard figured if Harry really had seen the saucers and the rays, then those rays were boredom rays. It would be a way for space critters to get at earth folks, boring them to death. Getting melted down by heat rays would have been better. That was at least quick, but being bored to death was sort of like being nibbled to death by ducks.

Leonard continued looking at the highway, trying to imagine flying saucers and boredom rays, but he couldn’t keep his mind on it. He finally focused on something in the highway. A dead dog.

Not just a dead dog. But a DEAD DOG. The mutt had been hit by a semi at least, maybe several. It looked as if it had rained dog. There were pieces of that pooch all over the concrete and one leg was lying on the curbing on the opposite side, stuck up in such a way that it seemed to be waving hello. Doctor Frankenstein with a grant from Johns Hopkins and assistance from NASA couldn’t have put that sucker together again.

Leonard leaned over to his faithful, drunk companion, Billy—known among the gang as Farto, because he was fart-lighting champion of Mud Creek—and said, “See that dog there?”

Farto looked where Leonard was pointing. He hadn’t noticed the dog before, and he wasn’t nearly as casual about it as Leonard. The puzzle-piece hound brought back memories. It reminded him of a dog he’d had when he was thirteen. A big, fine German Shepherd that loved him better than his Mama.

Sonofabitch dog tangled its chain through and over a barbed wire fence somehow and hung itself. When Farto found the dog its tongue looked like a stuffed, black sock and he could see where its claws had just been able to scrape the ground, but not quite enough to get a toe hold.

It looked as if the dog had been scratching out some sort of a coded message in the dirt. When Farto told his old man about it later, crying as he did, his old man laughed and said, “Probably a goddamn suicide note.”

Now, as he looked out at the highway, and his whiskey-laced Coke collected warmly in his gut, he felt a tear form in his eyes. Last time he’d felt that sappy was when he’d won the fart-lighting championship with a four-inch burner that singed the hairs of his ass and the gang awarded him with a pair of colored boxing shorts. Brown and yellow ones so he could wear them without having to change them too often.

So there they were, Leonard and Farto, parked outside the DQ, leaning on the hood of Leonard’s Impala, sipping Coke and whiskey, feeling bored and blue and horny, looking at a dead dog and having nothing to do but go to a show with a nigger starring in it. Which, to be up front, wouldn’t have been so bad if they’d had dates. Dates could make up for a lot of sins, or help make a few good ones, depending on one’s outlook.

But the night was criminal. Dates they didn’t have. Worse yet, wasn’t a girl in the entire high school would date them. Not even Marylou Flowers, and she had some kind of disease.

All this nagged Leonard something awful. He could see what the problem w

as with Farto. He was ugly. Had the kind of face that attracted flies. And though being fart-lighting champion of Mud Creek had a certain prestige among the gang, it lacked a certain something when it came to charming the gals.

But for the life of him, Leonard couldn’t figure his own problem. He was handsome, had some good clothes, and his car ran good when he didn’t buy that old cheap gas. He even had a few bucks in his jeans from breaking into washaterias. Yet his right arm had damn near grown to the size of his thigh from all the whacking off he did. Last time he’d been out with a girl had been a month ago, and as he’d been out with her along with nine other guys, he wasn’t rightly sure he could call that a date. He wondered about it so much, he’d asked Farto if he thought it qualified as a date. Farto, who had been fifth in line, said he didn’t think so, but if Leonard wanted to call it one, wasn’t no skin off his back.

But Leonard didn’t want to call it a date. It just didn’t have the feel of one, lacked that something special. There was no romance to it.

True, Big Red had called him Honey when he put the mule in the barn, but she called everyone Honey—except Stoney. Stoney was Possum Sweets, and he was the one who talked her into wearing the grocery bag with the mouth and eyeholes. Stoney was like that. He could sweet talk the camel out from under a sand nigger. When he got through chatting Big Red down, she was plumb proud to wear that bag.

When finally it came his turn to do Big Red, Leonard had let her take the bag off as a gesture of goodwill. That was a mistake. He just hadn’t known a good thing when he had it. Stoney had had the right idea. The bag coming off spoiled everything. With it on, it was sort of like balling the Lone Hippo or some such thing, but with the bag off, you were absolutely certain what you were getting, and it wasn’t pretty.

Even closing his eyes hadn’t helped. He found that the ugliness of that face had branded itself on the back of his eyeballs. He couldn’t even imagine the sack back over her head. All he could think about was that puffy, too-painted face with the sort of bad complexion that began at the bone.

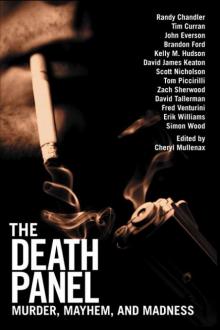

The Death Panel

The Death Panel Necro Files: Two Decades of Extreme Horror

Necro Files: Two Decades of Extreme Horror